Trip Report:

Snow Leopard

Photo Expedition

Trip Report

2016

That was it. Our snow leopard. Once again, the lack of snow kept the Blue Sheep and the Snow Leopards high in the high country. This leopard killed a sheep during the night, but wolves stole the kill, depriving us of any chance at getting close to the leopard. Scroll down to read the details and to see more images.

Before you see this elusive cat, tradition holds that the cat is only referred to obliquely, as ‘The Gray Ghost,’ or ‘The cat that shall not be named,’ as calling Panthera oncia by its common name might bring bad luck. Calling it the Gray Ghost is most appropriate, I think, as it truly is a phantom. In a land of towering mountains, sheer cliffs, and endless vistas of rock and snow, finding the Snow Leopard seems impossibly daunting, and seeing one seemingly is miraculous.

This was my third trip to the land of the Gray Ghost. On my first trip, I blew a truly spectacular opportunity when Mary and I chose to follow the original plan to visit a mountain village, when four others in that group wisely chose to go where a snow leopard had been reported at a kill. They shot what were probably, to them and to me, once in a lifetime shots. I photographed village life at a mountain homestay. As depressed as I was by the outcome of that trip, my spirits were buoyed, somewhat, when I met a European photographer who photographed that leopard and later, that same trip, shot images almost as good as the first opportunity. So, I believe, the chance still exists for good shots.

This year, just like last year’s trip, the area had no snow. On my first trip it was very cold, but snow blanketed much of the hillsides and with those conditions Blue Sheep, one of the Snow Leopard’s main prey items, were feeding down in the mountain valleys. In contrast, for the last two years the snows didn’t fall, and the hillsides were bare, and the sheep were high. And high on those same mountain tops, the Snow Leopards hunted.

Ironically, the beginning of our Snow Leopard expedition was postponed by a day because of snow. Leh, the departure city for our expedition, lies nestled in a valley surrounded by snow-covered Himalayan mountains. To fly in, pilots must have visual clearance, as a purely instrument landing in airspace surrounded by unforgiving ridges of rock could be suicidal. We flew into Leh, but on our final approach, as we banked and began our descent, a snow squall developed, reducing visibility to below flight safety standards and we were forced to return to Delhi. We waited on the tarmac there, hoping that conditions would improve and we’d get back into the air. After nearly two hours the flight was cancelled, and we returned to the Radisson for an overnight.

Day Two. Leh.

The following day the weather cleared and our flight went uneventfully. I had my cell phone out, all set to photograph the snow-capped mountains, the nearly unending line of ridges extending north to the horizon, but found that my window seat faced a blank wall! For those who had a view, it was spectacular, as the snow had just risen and the ridges were bathed in golden light, etched in deep shadows from the low angle of the sun.

We arrived in Leh, somewhat surprised that there was no evidence of the snowstorm that closed the airport yesterday. In this high desert, snow melts or evaporates directly quickly, and the mountain slopes, and the land below, was bare. Not a good omen.

Normally we have two days in Leh to adjust to the abrupt change in elevation, as Leh’s elevation is approximately 11,000 feet, and the air is thin. In these high elevations breathing is labored, and it is easy to feel winded, weak, or sick. I had a taste of this when we checked in to the Grand Dragon hotel, when I carried my camera gear and computer up three flights of steps to my room, planning on starting my conditioning. I felt winded, and almost nauseous, and although it went no further, it was a good warning for me to be careful from that point on.

Day Two, to Camp. Now one day short, we decided to head to base camp the following day, as the hike up the valley, about a two hour walk, is somewhat easy, and we could as easily acclimatize there as we could in Leh. We left at 9:30AM for the hour-plus drive to Hemis High Altitude Mountain Park. En route, we found a herd of Urial Sheep, grazing on the flatlands adjacent to steep, rolling hillsides. They were closer than we’ve ever had these sheep before, so we stopped, and after photographing them from the roadside we moved in closer to a dry gulch where we had some cover. The sheep were relatively unconcerned, and we had some fair shooting, but since the sheep were feeding on their winter range we didn’t wish to disturb them and instead left them to feed.

Day Two, to Camp. Now one day short, we decided to head to base camp the following day, as the hike up the valley, about a two hour walk, is somewhat easy, and we could as easily acclimatize there as we could in Leh. We left at 9:30AM for the hour-plus drive to Hemis High Altitude Mountain Park. En route, we found a herd of Urial Sheep, grazing on the flatlands adjacent to steep, rolling hillsides. They were closer than we’ve ever had these sheep before, so we stopped, and after photographing them from the roadside we moved in closer to a dry gulch where we had some cover. The sheep were relatively unconcerned, and we had some fair shooting, but since the sheep were feeding on their winter range we didn’t wish to disturb them and instead left them to feed.

Unfortunately, as we drove off, another vehicle stopped, and the occupants moved in close, with one guy walking straight towards the sheep. As we drove off the sheep were still present, so perhaps they would not have been disturbed. I didn’t wish to risk it.

We stopped at the overlook where the Indus River meets another ( ), the Indus muddy with sediment while the other river, fed from melting glaciers, is blue with glacial silt. A Golden Eagle soared passed, where, last year, we were surprised by a surprisingly close fly-by by a Lammergeir vulture. After shooting some scenic we drove on.

We reached our departure point, where our four taxis stopped to unload our luggage as we waited for a string of pack horses to arrive to carry the gear to camp. The horses arrived, mere ponies barely reaching much higher than our chest, and the stringer packed each with a huge load of bags and camera gear. Our walk began.

Reaching camp, I was surprised to find that we were the only ones camping. Last year, three different campsites were filled, and I expected the same this year. These crowds are somewhat problematic, as more guides mean more eyes looking for cats, but if one is found, then there’s a bigger crowd, and less freedom in trying to do anything with the cat. Lunch was ready when we arrived, a simple meal of rice and vegetables, and afterwards, most of the group hiked up to the observation hill where people normally stand and look for leopards. Konschok, my porter for the last three trips, and I headed back down the valley to a side canyon that I’ve always liked and where, in year’s past, we’d see snow leopard tracks. Still quite unconditioned to the altitude, I didn’t want to go far, and we moved only a few hundred yards into the canyon where we scoped the hillsides for cats. We saw nothing.

The landscape here, as George Schaller wrote in the title of one of his books, Stones of Silence, is a land of rock and silence. In this mountain valley the mountains rise steeply, precipitously, and for me at least, completely impossible to climb. The mountain slopes are a mix of hard, uneroded rock that rise like rugged islands in a sea of talus chop, broken stone and scree that surrounds each one of these rocky islands. Game trails of Blue Sheep criss-cross these talus slopes, as would Snow Leopards, who also use the rock islands as perches, lookouts, and resting places.

The landscape here, as George Schaller wrote in the title of one of his books, Stones of Silence, is a land of rock and silence. In this mountain valley the mountains rise steeply, precipitously, and for me at least, completely impossible to climb. The mountain slopes are a mix of hard, uneroded rock that rise like rugged islands in a sea of talus chop, broken stone and scree that surrounds each one of these rocky islands. Game trails of Blue Sheep criss-cross these talus slopes, as would Snow Leopards, who also use the rock islands as perches, lookouts, and resting places.

Day 3, Camp.

Enthusiastic and perhaps a bit naïve, most of the group got up early and headed for various lookout points to scan the slopes for leopards. Steve and I, veterans from past trips, stayed behind, counting on our spotters to see what we surely would miss. One of our group slept in, a bit overwhelmed by the cold and the altitude. When I crawled out of my tent and freshened up, I had a bit of a surprise when I tried brushing my teeth. During the night, the wet bristles of my toothbrush froze solid, and my first swipes with the brush was like using a paint scraper. In the future, I know I’ll soak the brush in warm water first.

On this trip, at least for the first two days, we were joined by our outfitter and by two of his employees, L-K, and Harri. L-K, who normally works in the Delhi office, has looked miserable from the start, probably affected by the altitude and the low oxygen. Harri, who leads excursions for the company, is a strong, fit, and young guy, who made the big mistake yesterday of walking fast, carrying his own pack and a scope and tripod, too. Often it is the best athletes or fittest people who run into trouble, as they push themselves more, and find, to their chagrin, that the altitude always wins.

Today, before breakfast, I walked back down the valley trail, passed the side valley and on towards the car park area, figuring no one was checking that area. Along the way I found L-K slowly ambling along, uncomfortable and hurting, and Harri, who was weaving along, stopping to stoop, hands on his knees, or resting his head upon a tall trailside boulder. Harri was supposed to stay with us as trip coordinator for the entire expedition, but he and the two others from the company will be returning to Leh today, and Harri, back to Delhi, to get back to a safer altitude. Right now, he’s in a bad way.

Leaving those two, I continued downhill, going slowly, scanning the rocks and appreciating, as best I could, the area’s geology. Along the mountain tops cap rocks project above the horizon, looking like human heads where the rock and conglomerate below them slowly erodes and narrows until, at some point, the caprock that compresses the column finally topples. Across from me, on one of these steep hillsides, a series of rocks form a step-like arrangement, but the steps are canted crazily, and walking these steps would require a severe inward tilt to maintain balance. Both above and below these steps is only scree, making this formation, as with so many others, unreachable.

We ate breakfast at 9:15, French toast and eggs, and headed towards the Pika Valley on the trail that leads to Rumbak. We arrived at the Pika rocks at 11:30 or so, with the rocks still in deep shadow. One, very shy, Big-eared Pika popped up periodically, but only showed itself for any length of time when it was at the far corner of the rock pile, close to the willows that line the stream. Some of the group headed into another valley, the one where four years ago the Snow Leopard had its great kill, and we planned on hiking to that location after lunch.

Blue Sheep were reported to be close, but as it often turns out with these messages, the guys that were on the lookout only had, at that time, rather distant views. When we arrived the Blue Sheep were fairly low on a distant slope, and we approached as close as we could until a canyon-like dry wash stopped any further progress. The sheep moved on, but actually came closer, eventually coming to the edge of the dry wash, then running in, climbing out and crossing the talus slope above us. We scrambled for good views, and had some decent close-up shots, and shots of sheep standing on the ridge line, framed by a impossibly blue sky.

Eventually the herd moved closer to the other group, but by then the light was fairly low and the shooting was only fair. One of our group, the second oldest in the party – I’m the oldest, this time, had hiked to the end of the Pika/Rumbak valley earlier in the day, then did the Pikas, and now the Sheep, but he was suffering by the time he tried scrambling up the slopes and I worried that we might have another Harri situation developing. Fortunately, he recovered.

Eventually the herd moved closer to the other group, but by then the light was fairly low and the shooting was only fair. One of our group, the second oldest in the party – I’m the oldest, this time, had hiked to the end of the Pika/Rumbak valley earlier in the day, then did the Pikas, and now the Sheep, but he was suffering by the time he tried scrambling up the slopes and I worried that we might have another Harri situation developing. Fortunately, he recovered.

I checked my GPS unit, the elevation reading 12,600 here. I had waypointed Leh and the Car Park, and found we were 10.5 miles, as the crow flies, from Leh, and 9.5 miles from the Car Park.

Our plan is to break camp tomorrow and head to Rumbak, the site of my big mistake four years ago, and where I hoped my luck would change. A group returning from Rumbak reported seeing three Snow Leopards, but far away, as well as an Asiatic Lynx and a few wolves. With no snow and no sense of any activity here, the change seems worthwhile. Our outfitter, who headed to Ulley for the day, had said that if anything good was spotted at Ulley, our final destination, we’d get a call and would head there immediately. How we’d get that call… something of a mystery.

Our plan is to break camp tomorrow and head to Rumbak, the site of my big mistake four years ago, and where I hoped my luck would change. A group returning from Rumbak reported seeing three Snow Leopards, but far away, as well as an Asiatic Lynx and a few wolves. With no snow and no sense of any activity here, the change seems worthwhile. Our outfitter, who headed to Ulley for the day, had said that if anything good was spotted at Ulley, our final destination, we’d get a call and would head there immediately. How we’d get that call… something of a mystery.

Day 4, Rumbak Camp.

The plan was to break camp at 8:30 and head to Rumbak, but the horses had not yet arrived at 9:30 as we waited. The entire camp was dismantled, and would be reassembled at Rumbak. At 10 we headed out, and after passing through the Pika rocks I spotted a Pika right beside the trail. The animal was quite tame, and posed on rocks close to the trail for photos.

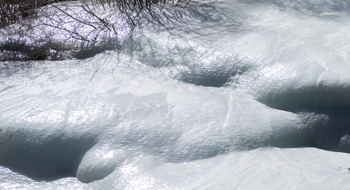

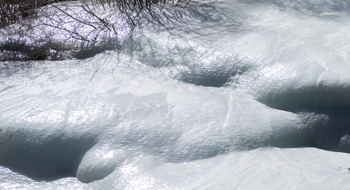

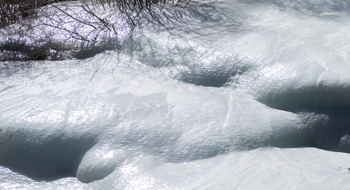

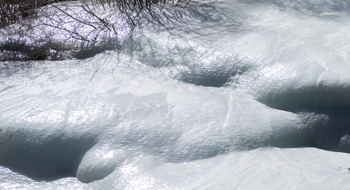

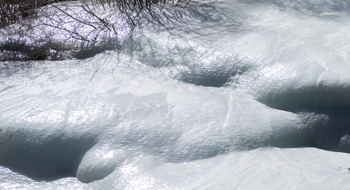

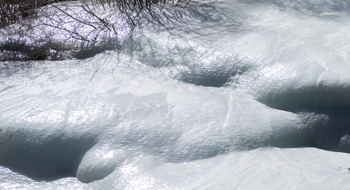

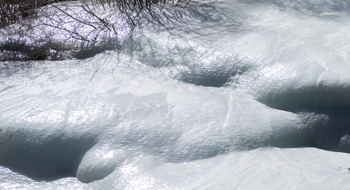

Our trail took us across the small stream that leads from Rumbak. It is frozen solid now, although standing on the ice I can hear the stream rushing below, hidden by the ice. The river resembles Yellowstone flowstone, gypsum, as if in a flash the river just went solid. Ripples, small water falls, curves and eddies, all frozen in time, and still in the shade of morning the blue ice glints golden at times, reflecting the cliffs high above catching the morning light.

Our trail took us across the small stream that leads from Rumbak. It is frozen solid now, although standing on the ice I can hear the stream rushing below, hidden by the ice. The river resembles Yellowstone flowstone, gypsum, as if in a flash the river just went solid. Ripples, small water falls, curves and eddies, all frozen in time, and still in the shade of morning the blue ice glints golden at times, reflecting the cliffs high above catching the morning light.

We reached camp by lunch, at an elevation of 12,700 feet, about 800 feet higher than our last camp. The campsite is an established one, with a stone outhouse with two stalls, where we’ll place our portable camp toilet and a ‘thunder box’ – no explanation needed, to save our knees from the traditional Asian squat. Right before we reached the end of the Rumbak gorge Konshok pointed out a ledge where only a month ago a Snow Leopard had fed upon a Blue Sheep kill. He, Chitta, and Morup got a phone call, and left that day for Rumbak, staying overnight at the homestay and photographing the cat the next morning. It was less than 100 yards from the trail, at eye-level, and they were the only ones there. Konshok used his old camera, and I wish he had had the new Canon that I brought him, one with a 1200mm optical zoom that he just loves.

The camp was set up in less than 1.5 hours, with our tents strung out in a line from the kitchen tent to the outhouse. Fortunately, with the cold, there is no odor. The campsite may also function as a pasture, as tiny bits of grass or weed or straw cling to virtually everything. Unlike our previous campsite, this one feels dirty, simply because of the straw. Again, the skies are cloudless, and the night promises to be very cold as the earth’s radiant heat drains into the night sky.

While we were standing about a number of Blue Sheep appeared on a nearby ridge, running downslope, presumably to get a drink. The running generated some excitement, as some speculated that a Snow Leopard had spooked them, but I’ve seen Big Horns in Yellowstone run with the same enthusiasm to reach water late in the day. Our guides, meanwhile, are manning several hills, scopes at hand, scanning the slopes for cats.

While we were standing about a number of Blue Sheep appeared on a nearby ridge, running downslope, presumably to get a drink. The running generated some excitement, as some speculated that a Snow Leopard had spooked them, but I’ve seen Big Horns in Yellowstone run with the same enthusiasm to reach water late in the day. Our guides, meanwhile, are manning several hills, scopes at hand, scanning the slopes for cats.

Day 5, Rumbak Camp.

Surprisingly, my water bottle, kept outside my sleeping bag, did not freeze overnight as it had on our first trip four years ago. Our campsite is situated at the juncture of two valleys, one leading to Rumbak, the other into the mountainous interior where several other valleys join this major valley. Our goal today is to explore this valley, hiking along the frozen river’s edge. Marup, one of our guides, pointed out an old Snow Leopard scrape, but there was no recent sign.

The river we followed is about 150 yards wide, braided with glacial stones, and reminding me of the river at Denali that shares similar features. The valley terminates, or so it appears, in a bowl of mountains, and it looks like only a rise of 300 feet or so would bring one to the snow line. In reality, as distances are so misleading here, it is probably 900 feet. Again, the geology is impressive, with rock folds sometimes forming sweeping S shapes and Z’s, like a blanket or sheet pushed and scrunched on a bed, folding into odd shapes, a miniature of the earth before me.

A side valley joined the broad river valley, leading uphill at a modest incline but taking us deeper into the high country. Most of us took this route, which led to what is now another Home Stay, but once was either a monastery or a warlord’s palace – depending upon the story. Steep cliffs bordered a frozen river that led from this high country, with some areas reminiscent of Goblin Valley, with solid cap rocks compressing the conglomerate rock beneath it, forming spires or very narrow pyramid shapes. A Lammergeir, a huge vulture that is sometimes referred to as a bone-breaker for its habit of picking up large bones, flying high, and dropping the bones onto rocks to shatter the bones for the marrow inside. The Lammergeir flew up the valley, did a U-turn, and flew directly overhead, quite close, and probably only 80 feet above me. I had my Olympus 4/3rds camera and a 150-300 (equivalent 300-600) but the battery apparently was dying and the lens would not acquire focus. In desperation I shot one out-of-focus shot, and then the battery went dead. For the rest of the day I carried the dead weight of several lenses and a useless camera.

A side valley joined the broad river valley, leading uphill at a modest incline but taking us deeper into the high country. Most of us took this route, which led to what is now another Home Stay, but once was either a monastery or a warlord’s palace – depending upon the story. Steep cliffs bordered a frozen river that led from this high country, with some areas reminiscent of Goblin Valley, with solid cap rocks compressing the conglomerate rock beneath it, forming spires or very narrow pyramid shapes. A Lammergeir, a huge vulture that is sometimes referred to as a bone-breaker for its habit of picking up large bones, flying high, and dropping the bones onto rocks to shatter the bones for the marrow inside. The Lammergeir flew up the valley, did a U-turn, and flew directly overhead, quite close, and probably only 80 feet above me. I had my Olympus 4/3rds camera and a 150-300 (equivalent 300-600) but the battery apparently was dying and the lens would not acquire focus. In desperation I shot one out-of-focus shot, and then the battery went dead. For the rest of the day I carried the dead weight of several lenses and a useless camera.

My Lammergeir! Adding this photo is a lame bit of humor.

Continuing on, we reached the Home Stay at 13,670 feet, perhaps the highest elevation I’d reach in the Rumbak area. If this was a warlord’s palace, one has to wonder who he’d be fighting, as the land had to always be rather barren. A Stupa, a stone, dome-like structure, had a few ungulate skulls along a ledge, with one quite out of place. The skull belonged to a Tibetan Argali, a Bighorn Sheep relative that Marup, one of our guides, said sometimes wander into this valley.

At the far end of the valley, and what looked like nearly a mile away, a large ram Blue Sheep stood motionless. Konchok took a photo with his new camera, at 1200mm, and I was absolutely stunned at the size of the image. For an amateur desiring record shots, it’s a great camera.

Our elevation gain to the Home Stay was about 500 feet, on a trail that we took casually, especially when one is just looking at the ground before you. I twisted my ankle, just losing my balance a bit, and it was only then that I really took note of our trail. Most of the time the trail paralleled the stream valley, sometimes thirty feet, sometimes fifty or more feet above the frozen stream. The gradient was steep, at least 70 degrees, so a trip or fall would have been a disaster.

Our elevation gain to the Home Stay was about 500 feet, on a trail that we took casually, especially when one is just looking at the ground before you. I twisted my ankle, just losing my balance a bit, and it was only then that I really took note of our trail. Most of the time the trail paralleled the stream valley, sometimes thirty feet, sometimes fifty or more feet above the frozen stream. The gradient was steep, at least 70 degrees, so a trip or fall would have been a disaster.

The rest of the day’s hike went uneventfully, and we returned to camp in the late afternoon. One of the guys on the trip, a former recon-soldier in the British army, had hiked up another one of the side canyons and found two wolves which he followed for about 500 yards. Unfortunately he only had a 24-70mm zoom with him, but the shots, cropped hugely, were okay, so he’d have had great images with the 200-400mm he still had in his pack.

At 6 all but our ex-soldier were back in camp when we got the exciting news that a Snow Leopard had been spotted. Our guides and spotters were on a small rise just above our camp, and the younger guys in our group practically ran up the hill, probably a 60 foot rise in elevation, and, of course, nearly died by doing so. Exertion, like running, is tough for most of us at 12,000 feet, and they spent the next few minutes gasping. Me, I walked up, as fast as I could, but stopping occasionally, and this time, the tortoise (me) may have won the race, or at least I wasn’t dying from the walk. The young guys recovered fast, nonetheless.

My porter, Konshok, was already setting up my tripod and lens, and as I approached the group gathered around, facing a slope, I worried that the cat was close, and I had missed it. I was wrong on both counts – the Snow Leopard, when one of the spotters aimed my lens at it, was nearly a mile away, and only the top of its head was visible. We put our Swarovski scope on the cat, and I did a Live View with my camera, then magnified that image by 10X, so we had a somewhat decent view of the far away cat. Several people with small lenses or binoculars gathered around my Live View image, and enjoyed a nice view when the cat finally got up, stretched, and walked down the ridge, finally disappearing behind the slope. It was our first cat, and we hoped that seeing this one would break the ice and we’d start to have great luck.

Day 6. Rumbak. We awoke to cloudy skies, with snow threatening the higher slopes. Last evening, as the last guys were leaving the slope, they spotted an Eagle-Owl on a ledge. The owl flew off, but merely seeing one of these birds this high was surprising, as I’ve seen virtually no sign of small mammals for the bird to eat.

Last night I changed strategies for a more comfortable winter survival, camping, night, wrapping the clothes I’d wear the following day around the two hot-water bottles we’re given, and using a hand-warmer in with my batteries. Trying to stack the odds for our luck, I extracted the small plastic Snow Leopard model I’d brought along, and I wore my Snow Leopard goofy hat beneath my baklava, and combined, the two pieces of head gear kept me warm throughout the night.

Our plan today was to hike up the same valley we explored yesterday, hopefully to find the Snow Leopard at a kill. I packed my ice crampons along, just in case, and as it turned out I was glad I did.

We had passed beyond the side canyon we visited yesterday when we received word that something was happening ahead. To reach this destination, most of us crossed the frozen river, which would have been extremely hazardous if not for the crampons. Chitta, one of our guides, told me we had no time to waste on crampons, but I knew my limitations and ignored his advice. Without them, my boots slid across the ice like Bambi on a frozen lake, and I’d have either fallen or jerked myself about trying to keep my balance on the slick ice. With them, the walk was easy and fun, and to insure my gear I held on to Konshok, who like the other guides simply balance themselves and walk across the ice. One slip, however, and my scope and 800mm would be toast, so it was prudent to hold on to Konshok.

As it turned out our destination was the original side of the river, so we crossed the ice once again. I still had no idea what we were after, but I assumed it was a Leopard. Another hiking group had preceded our’s, and they were set up and aiming up a hill. As I approached they motioned for me to get down, so I hunched over and stalked forward until I could join them.

On a distant hillside a Gray Wolf was feeding on a Blue Sheep, with another Wolf lying on a rock further up the hill. We  assume that ‘our’ Snow Leopard had made the kill but the Wolves discovered it and drove the cat off. We watched the wolf from three hundred yards or so, and with at least two groups lined up it was impossible to even attempt to get closer. Eventually the wolves took off with pieces, one taking a leg, while the other Wolf carried the remains of the carcass – head, neck, and at least the front half of the body – up a steep scree slope, seemingly effortlessly, and disappearing from sight.

assume that ‘our’ Snow Leopard had made the kill but the Wolves discovered it and drove the cat off. We watched the wolf from three hundred yards or so, and with at least two groups lined up it was impossible to even attempt to get closer. Eventually the wolves took off with pieces, one taking a leg, while the other Wolf carried the remains of the carcass – head, neck, and at least the front half of the body – up a steep scree slope, seemingly effortlessly, and disappearing from sight.

With the wolves gone we had lunch, as the distant slopes became shrouded in snow clouds, weather that soon reached us. The camp staff carried up lunch, tea, soup, bread, and some meat, while the porters gathered whatever vegetation they could find, and yak dung, to make a fire where they heated their food and squatted around, warming their hands. It began to snow heavily, and with the low cloud cover that we had all morning I doubted if Mary would be flying in to Leh to join me for our trip to Ulley. The ex-soldier and one of the other younger guys in our group, a former Ironman competitor, decided to go for the wolves, and after lunch hiked up the steep mountainside. Eventually they reached the very top of the ridge where they looked down, very far below, on the Guest House we visited yesterday. The view was impressive, the isolation sublime, and that hike, for them, was one of the trip highlights.

With the wolves gone we had lunch, as the distant slopes became shrouded in snow clouds, weather that soon reached us. The camp staff carried up lunch, tea, soup, bread, and some meat, while the porters gathered whatever vegetation they could find, and yak dung, to make a fire where they heated their food and squatted around, warming their hands. It began to snow heavily, and with the low cloud cover that we had all morning I doubted if Mary would be flying in to Leh to join me for our trip to Ulley. The ex-soldier and one of the other younger guys in our group, a former Ironman competitor, decided to go for the wolves, and after lunch hiked up the steep mountainside. Eventually they reached the very top of the ridge where they looked down, very far below, on the Guest House we visited yesterday. The view was impressive, the isolation sublime, and that hike, for them, was one of the trip highlights.

As we ate up the time after lunch I studied the landscape, which looked as if it could be on Mars. The land is barren, with a thin, straw-like grass covering some areas, and a tiny, tumble-weed plant that added a bit of orange-yellow color, and the only cover, on the scree slopes. In summer, I suspect goats and sheep graze here, but the grazing must be poor and the living very, very hard.

The rest of us slowly made our way back down to camp, as the snow fell, making footing somewhat treacherous. Shortly after reaching camp it stopped snowing, but the day remained cloudy. The day, now sunless, grew cold and I put on everything I had, as snow continued to intermittently fall through the evening and throughout the night.

Day 7. Rumbak to Leh

We awoke to about an inch of snow covering the tents and ground, the conditions we wished we’d had for the entire week of camping. Without snow, the Blue Sheep stay high on the ridges, as do the Snow Leopards, and now, with near perfect conditions we’re heading back to Leh. In theory, if the guides spotted anything we’d delay our departure and photograph, but since our taxis were already booked I suspect that there wasn’t too much effort spent in searching for cats. We left camp around 9:30, packed up and ready for the horses to arrive.

Hiking out, we had snow, and visibility was very limited. While the trail never seemed dangerous, the fact is that we were often on slopes that would pitch an unwary hiker thirty or fifty feet down onto the rocks or stream below. I paused often to scan the hillsides, or cliffs, but saw nothing. It took only an hour or so to reach our original camp site, still deserted, and with no animals visible on the slopes above.

Our trip back to the car park from this camp required another hour or so, and we arrived long before our scheduled pickup time. The road here was icy and snow covered, and I wondered if our taxis would make it up the hill. The entire return was a fairly effortless walk since most of it was downhill. New groups were hiking up as we headed down, and one guy, in his fifties or sixties and appearing a bit over-weight, looked like he was really suffering, and this only a few hundred yards up from the car park.

We waited nearly an hour before the first taxi arrived, and in a not very encouraging introduction the vehicle slipped and stayed stuck on the final stretch of roadway. With the help of guides and porters they pushed the taxi free, and, thankfully, started chaining up the tires for our return to Leh.

Sanzkar river and Indus – intersection.

We reached Leh in time for a late lunch. I turned in laundry, racking up a $60 bill, but well worth it, as I couldn’t imagine putting on the same, five-day old clothes, for another two days in Ulley.

Day 8. To Ulley

We left Leh at 9:30AM, planning a long drive to Ulley where, en route, we’d stop to scan for Snow Leopards. On our drive we encountered a nice herd of Urial Sheep, and we left the road for about half-frame shots. Snow covered the north and east facing slopes, and south and west the rocks were bare. The sky was crystal clear, and I was relieved, as with the bad weather yesterday Mary’s flight was cancelled and she wisely chose to remain in Delhi for the next three nights, rather than join me and be at 13,000 feet almost immediately.

We arrived in Ulley in the late afternoon, and unlike last year, when we had snow leopard tracks along the road, the snow was track-free. After settling in, our guides took positions at several vantage points and scanned for cats, but we saw none. Instead, a difficult-to-see herd of Asiatic Ibex grazed far above us.

Day 9. Ulley

Day 9. Ulley

The Home Stay is quite a bit more pleasant than camping. Our rooms had electric heat – portable heaters we were asked to turn off at night, but in the evening hours the heaters helped warm the rooms. Phil, Gordie, and Tommy shared one large room, that also functioned as our meeting area and dining room. Danni and Steve and Andrew were in adjacent rooms, and all shared an outdoor bathroom where toilet seats – versus squatting – were provided. I was staying in a guest room in the main house, and used the family’s facilities, a slit I trench in a walled enclosure, with no roof and a good view of the rooftop of the house nearby.

After breakfast we drove, thankfully, uphill to the last house on the hill, a location we hiked to four years ago. The road was snowy and icy in spots, and required fording a stream that was mostly frozen. However, the drive took us to the highest country, before we continued on, on foot, climbing a rock outcrop for another 700 feet or so. We were looking for snow leopards and ibex, and at 14,600 feet we stopped, as the route higher from that position was too treacherous. We were on snow and rock, with the rocks composed of a sandstone-like conglomerate, appearing to be solid rock but with a gravelly sheen that sometimes slipped, causing treacherous footing. Chitta cautioned us to go no higher by that route.

We could see Ibex, about a mile away and further up slope, and while I was at a higher position Steve, Andrew, and Marup decided to try for the Ibex. To do so, they had to descend the rocks, then climb uphill again, and when I finally saw them, I felt the effort would be useless. Chronic dry sinuses and a developing chest cough didn’t help in my decision, but I didn’t think Steve would be successful. Tommy decided to join them and started down and across the rocks. The going, Steve reported, was tough, with the rocks often snow-covered, and the ground frozen solid and slick. Under Steve’s urging they continued to move closer, and to my amazement the Ibex didn’t seem to mind. Chitta, the guide who remained with us, thought that the Ibex would run high, or to our right, or perhaps to our left, where they could come close to us. They didn’t do any of those choices, and instead continued to graze. Eventually, Steve, with a 600mm and 2X converter, captured nearly half-frame shots of the Ibex, so the effort was certainly worth it.

When everyone returned to the Home Stay, I casually remarked to Marup that they had had great luck, and I was surprised that the Ibex didn’t run off. Marup replied that he had called the owner of the Home Stay, who told him that the Ibex used to be wary, but now were fairly tame and approachable. I didn’t ask our guide when he learned that information – was it during the hike to the Ibex, was it before they even started, or was it on their way down – but either way, it was too late for the rest of us to consider going for the Ibex. And for the three who made the hike, covering rough country that may have been avoided – as their hike down was direct, easy, and on a gradual slope, knowing that an easier route may have been possible was a bit annoying.

We spent the rest of the afternoon either relaxing or glassing the slopes for cats, while our three guides, and my porter, spent the entire time at the scopes, as the light dropped, a wind picked up, and the cold descended. Only after the sun dropped below the mountains, and the light was gone, did they quit – I was very impressed with their efforts.

Day 10. Ulley to Leh

The plan was, if nothing was spotted from Ulley we’d slowly drive back to Leh, pausing often to scope the hillsides for snow leopards. Yesterday, a hiking group had been dropped off at Ulley, where the group would then descend the trail paralleling the stream valley and eventually meet their vehicles below. One of the group told me that just a half hour after they had started their trip they had had an hour’s viewing of a snow leopard basking on a ledge, with the cat finally standing and climbing the ridge and passing out of sight. I later learned that their location was where we had our lunch on our way to Ulley, a great location with wide-open views. I didn’t ask how close they’d been to the cat – I didn’t need to know.

Although we stopped at a few locations, the plan, I felt, was a bust, as we arrived back in Leh around lunchtime – not late in the afternoon as I’d have expected. We had no significant sightings of wildlife on the way back, but I think everyone was, by then, tired and accepting of our outcome.

For snow leopards, this trip, this year, was disappointing, as we only had one sighting, and our record was somewhat typical of the luck people were having this year. The culprit – no snow, and the sheep and the cats were high. For the other wildlife, the Pika, Urial, Blue Sheep, Ibex,Wolves, Lammergeir, and Chukars, we were more successful than last year, and everyone felt the trip itself was a success, as the landscape, the company, and the experience was worth it.

After this trip, Steve and I continued into central India, for what would turn out to be an extremely successful mini-Safari for Tigers.

Trip Report:

Snow Leopard

Photo Expedition

Trip Report

2016

That was it. Our snow leopard. Once again, the lack of snow kept the Blue Sheep and the Snow Leopards high in the high country. This leopard killed a sheep during the night, but wolves stole the kill, depriving us of any chance at getting close to the leopard. Scroll down to read the details and to see more images.

Before you see this elusive cat, tradition holds that the cat is only referred to obliquely, as ‘The Gray Ghost,’ or ‘The cat that shall not be named,’ as calling Panthera oncia by its common name might bring bad luck. Calling it the Gray Ghost is most appropriate, I think, as it truly is a phantom. In a land of towering mountains, sheer cliffs, and endless vistas of rock and snow, finding the Snow Leopard seems impossibly daunting, and seeing one seemingly is miraculous.

This was my third trip to the land of the Gray Ghost. On my first trip, I blew a truly spectacular opportunity when Mary and I chose to follow the original plan to visit a mountain village, when four others in that group wisely chose to go where a snow leopard had been reported at a kill. They shot what were probably, to them and to me, once in a lifetime shots. I photographed village life at a mountain homestay. As depressed as I was by the outcome of that trip, my spirits were buoyed, somewhat, when I met a European photographer who photographed that leopard and later, that same trip, shot images almost as good as the first opportunity. So, I believe, the chance still exists for good shots.

This year, just like last year’s trip, the area had no snow. On my first trip it was very cold, but snow blanketed much of the hillsides and with those conditions Blue Sheep, one of the Snow Leopard’s main prey items, were feeding down in the mountain valleys. In contrast, for the last two years the snows didn’t fall, and the hillsides were bare, and the sheep were high. And high on those same mountain tops, the Snow Leopards hunted.

Ironically, the beginning of our Snow Leopard expedition was postponed by a day because of snow. Leh, the departure city for our expedition, lies nestled in a valley surrounded by snow-covered Himalayan mountains. To fly in, pilots must have visual clearance, as a purely instrument landing in airspace surrounded by unforgiving ridges of rock could be suicidal. We flew into Leh, but on our final approach, as we banked and began our descent, a snow squall developed, reducing visibility to below flight safety standards and we were forced to return to Delhi. We waited on the tarmac there, hoping that conditions would improve and we’d get back into the air. After nearly two hours the flight was cancelled, and we returned to the Radisson for an overnight.

Day Two. Leh.

The following day the weather cleared and our flight went uneventfully. I had my cell phone out, all set to photograph the snow-capped mountains, the nearly unending line of ridges extending north to the horizon, but found that my window seat faced a blank wall! For those who had a view, it was spectacular, as the snow had just risen and the ridges were bathed in golden light, etched in deep shadows from the low angle of the sun.

We arrived in Leh, somewhat surprised that there was no evidence of the snowstorm that closed the airport yesterday. In this high desert, snow melts or evaporates directly quickly, and the mountain slopes, and the land below, was bare. Not a good omen.

Normally we have two days in Leh to adjust to the abrupt change in elevation, as Leh’s elevation is approximately 11,000 feet, and the air is thin. In these high elevations breathing is labored, and it is easy to feel winded, weak, or sick. I had a taste of this when we checked in to the Grand Dragon hotel, when I carried my camera gear and computer up three flights of steps to my room, planning on starting my conditioning. I felt winded, and almost nauseous, and although it went no further, it was a good warning for me to be careful from that point on.

Day Two, to Camp. Now one day short, we decided to head to base camp the following day, as the hike up the valley, about a two hour walk, is somewhat easy, and we could as easily acclimatize there as we could in Leh. We left at 9:30AM for the hour-plus drive to Hemis High Altitude Mountain Park. En route, we found a herd of Urial Sheep, grazing on the flatlands adjacent to steep, rolling hillsides. They were closer than we’ve ever had these sheep before, so we stopped, and after photographing them from the roadside we moved in closer to a dry gulch where we had some cover. The sheep were relatively unconcerned, and we had some fair shooting, but since the sheep were feeding on their winter range we didn’t wish to disturb them and instead left them to feed.

Day Two, to Camp. Now one day short, we decided to head to base camp the following day, as the hike up the valley, about a two hour walk, is somewhat easy, and we could as easily acclimatize there as we could in Leh. We left at 9:30AM for the hour-plus drive to Hemis High Altitude Mountain Park. En route, we found a herd of Urial Sheep, grazing on the flatlands adjacent to steep, rolling hillsides. They were closer than we’ve ever had these sheep before, so we stopped, and after photographing them from the roadside we moved in closer to a dry gulch where we had some cover. The sheep were relatively unconcerned, and we had some fair shooting, but since the sheep were feeding on their winter range we didn’t wish to disturb them and instead left them to feed.

Unfortunately, as we drove off, another vehicle stopped, and the occupants moved in close, with one guy walking straight towards the sheep. As we drove off the sheep were still present, so perhaps they would not have been disturbed. I didn’t wish to risk it.

We stopped at the overlook where the Indus River meets another ( ), the Indus muddy with sediment while the other river, fed from melting glaciers, is blue with glacial silt. A Golden Eagle soared passed, where, last year, we were surprised by a surprisingly close fly-by by a Lammergeir vulture. After shooting some scenic we drove on.

We reached our departure point, where our four taxis stopped to unload our luggage as we waited for a string of pack horses to arrive to carry the gear to camp. The horses arrived, mere ponies barely reaching much higher than our chest, and the stringer packed each with a huge load of bags and camera gear. Our walk began.

Reaching camp, I was surprised to find that we were the only ones camping. Last year, three different campsites were filled, and I expected the same this year. These crowds are somewhat problematic, as more guides mean more eyes looking for cats, but if one is found, then there’s a bigger crowd, and less freedom in trying to do anything with the cat. Lunch was ready when we arrived, a simple meal of rice and vegetables, and afterwards, most of the group hiked up to the observation hill where people normally stand and look for leopards. Konschok, my porter for the last three trips, and I headed back down the valley to a side canyon that I’ve always liked and where, in year’s past, we’d see snow leopard tracks. Still quite unconditioned to the altitude, I didn’t want to go far, and we moved only a few hundred yards into the canyon where we scoped the hillsides for cats. We saw nothing.

The landscape here, as George Schaller wrote in the title of one of his books, Stones of Silence, is a land of rock and silence. In this mountain valley the mountains rise steeply, precipitously, and for me at least, completely impossible to climb. The mountain slopes are a mix of hard, uneroded rock that rise like rugged islands in a sea of talus chop, broken stone and scree that surrounds each one of these rocky islands. Game trails of Blue Sheep criss-cross these talus slopes, as would Snow Leopards, who also use the rock islands as perches, lookouts, and resting places.

The landscape here, as George Schaller wrote in the title of one of his books, Stones of Silence, is a land of rock and silence. In this mountain valley the mountains rise steeply, precipitously, and for me at least, completely impossible to climb. The mountain slopes are a mix of hard, uneroded rock that rise like rugged islands in a sea of talus chop, broken stone and scree that surrounds each one of these rocky islands. Game trails of Blue Sheep criss-cross these talus slopes, as would Snow Leopards, who also use the rock islands as perches, lookouts, and resting places.

Day 3, Camp.

Enthusiastic and perhaps a bit naïve, most of the group got up early and headed for various lookout points to scan the slopes for leopards. Steve and I, veterans from past trips, stayed behind, counting on our spotters to see what we surely would miss. One of our group slept in, a bit overwhelmed by the cold and the altitude. When I crawled out of my tent and freshened up, I had a bit of a surprise when I tried brushing my teeth. During the night, the wet bristles of my toothbrush froze solid, and my first swipes with the brush was like using a paint scraper. In the future, I know I’ll soak the brush in warm water first.

On this trip, at least for the first two days, we were joined by our outfitter and by two of his employees, L-K, and Harri. L-K, who normally works in the Delhi office, has looked miserable from the start, probably affected by the altitude and the low oxygen. Harri, who leads excursions for the company, is a strong, fit, and young guy, who made the big mistake yesterday of walking fast, carrying his own pack and a scope and tripod, too. Often it is the best athletes or fittest people who run into trouble, as they push themselves more, and find, to their chagrin, that the altitude always wins.

Today, before breakfast, I walked back down the valley trail, passed the side valley and on towards the car park area, figuring no one was checking that area. Along the way I found L-K slowly ambling along, uncomfortable and hurting, and Harri, who was weaving along, stopping to stoop, hands on his knees, or resting his head upon a tall trailside boulder. Harri was supposed to stay with us as trip coordinator for the entire expedition, but he and the two others from the company will be returning to Leh today, and Harri, back to Delhi, to get back to a safer altitude. Right now, he’s in a bad way.

Leaving those two, I continued downhill, going slowly, scanning the rocks and appreciating, as best I could, the area’s geology. Along the mountain tops cap rocks project above the horizon, looking like human heads where the rock and conglomerate below them slowly erodes and narrows until, at some point, the caprock that compresses the column finally topples. Across from me, on one of these steep hillsides, a series of rocks form a step-like arrangement, but the steps are canted crazily, and walking these steps would require a severe inward tilt to maintain balance. Both above and below these steps is only scree, making this formation, as with so many others, unreachable.

We ate breakfast at 9:15, French toast and eggs, and headed towards the Pika Valley on the trail that leads to Rumbak. We arrived at the Pika rocks at 11:30 or so, with the rocks still in deep shadow. One, very shy, Big-eared Pika popped up periodically, but only showed itself for any length of time when it was at the far corner of the rock pile, close to the willows that line the stream. Some of the group headed into another valley, the one where four years ago the Snow Leopard had its great kill, and we planned on hiking to that location after lunch.

Blue Sheep were reported to be close, but as it often turns out with these messages, the guys that were on the lookout only had, at that time, rather distant views. When we arrived the Blue Sheep were fairly low on a distant slope, and we approached as close as we could until a canyon-like dry wash stopped any further progress. The sheep moved on, but actually came closer, eventually coming to the edge of the dry wash, then running in, climbing out and crossing the talus slope above us. We scrambled for good views, and had some decent close-up shots, and shots of sheep standing on the ridge line, framed by a impossibly blue sky.

Eventually the herd moved closer to the other group, but by then the light was fairly low and the shooting was only fair. One of our group, the second oldest in the party – I’m the oldest, this time, had hiked to the end of the Pika/Rumbak valley earlier in the day, then did the Pikas, and now the Sheep, but he was suffering by the time he tried scrambling up the slopes and I worried that we might have another Harri situation developing. Fortunately, he recovered.

Eventually the herd moved closer to the other group, but by then the light was fairly low and the shooting was only fair. One of our group, the second oldest in the party – I’m the oldest, this time, had hiked to the end of the Pika/Rumbak valley earlier in the day, then did the Pikas, and now the Sheep, but he was suffering by the time he tried scrambling up the slopes and I worried that we might have another Harri situation developing. Fortunately, he recovered.

I checked my GPS unit, the elevation reading 12,600 here. I had waypointed Leh and the Car Park, and found we were 10.5 miles, as the crow flies, from Leh, and 9.5 miles from the Car Park.

Our plan is to break camp tomorrow and head to Rumbak, the site of my big mistake four years ago, and where I hoped my luck would change. A group returning from Rumbak reported seeing three Snow Leopards, but far away, as well as an Asiatic Lynx and a few wolves. With no snow and no sense of any activity here, the change seems worthwhile. Our outfitter, who headed to Ulley for the day, had said that if anything good was spotted at Ulley, our final destination, we’d get a call and would head there immediately. How we’d get that call… something of a mystery.

Our plan is to break camp tomorrow and head to Rumbak, the site of my big mistake four years ago, and where I hoped my luck would change. A group returning from Rumbak reported seeing three Snow Leopards, but far away, as well as an Asiatic Lynx and a few wolves. With no snow and no sense of any activity here, the change seems worthwhile. Our outfitter, who headed to Ulley for the day, had said that if anything good was spotted at Ulley, our final destination, we’d get a call and would head there immediately. How we’d get that call… something of a mystery.

Day 4, Rumbak Camp.

The plan was to break camp at 8:30 and head to Rumbak, but the horses had not yet arrived at 9:30 as we waited. The entire camp was dismantled, and would be reassembled at Rumbak. At 10 we headed out, and after passing through the Pika rocks I spotted a Pika right beside the trail. The animal was quite tame, and posed on rocks close to the trail for photos.

Our trail took us across the small stream that leads from Rumbak. It is frozen solid now, although standing on the ice I can hear the stream rushing below, hidden by the ice. The river resembles Yellowstone flowstone, gypsum, as if in a flash the river just went solid. Ripples, small water falls, curves and eddies, all frozen in time, and still in the shade of morning the blue ice glints golden at times, reflecting the cliffs high above catching the morning light.

Our trail took us across the small stream that leads from Rumbak. It is frozen solid now, although standing on the ice I can hear the stream rushing below, hidden by the ice. The river resembles Yellowstone flowstone, gypsum, as if in a flash the river just went solid. Ripples, small water falls, curves and eddies, all frozen in time, and still in the shade of morning the blue ice glints golden at times, reflecting the cliffs high above catching the morning light.

We reached camp by lunch, at an elevation of 12,700 feet, about 800 feet higher than our last camp. The campsite is an established one, with a stone outhouse with two stalls, where we’ll place our portable camp toilet and a ‘thunder box’ – no explanation needed, to save our knees from the traditional Asian squat. Right before we reached the end of the Rumbak gorge Konshok pointed out a ledge where only a month ago a Snow Leopard had fed upon a Blue Sheep kill. He, Chitta, and Morup got a phone call, and left that day for Rumbak, staying overnight at the homestay and photographing the cat the next morning. It was less than 100 yards from the trail, at eye-level, and they were the only ones there. Konshok used his old camera, and I wish he had had the new Canon that I brought him, one with a 1200mm optical zoom that he just loves.

The camp was set up in less than 1.5 hours, with our tents strung out in a line from the kitchen tent to the outhouse. Fortunately, with the cold, there is no odor. The campsite may also function as a pasture, as tiny bits of grass or weed or straw cling to virtually everything. Unlike our previous campsite, this one feels dirty, simply because of the straw. Again, the skies are cloudless, and the night promises to be very cold as the earth’s radiant heat drains into the night sky.

While we were standing about a number of Blue Sheep appeared on a nearby ridge, running downslope, presumably to get a drink. The running generated some excitement, as some speculated that a Snow Leopard had spooked them, but I’ve seen Big Horns in Yellowstone run with the same enthusiasm to reach water late in the day. Our guides, meanwhile, are manning several hills, scopes at hand, scanning the slopes for cats.

While we were standing about a number of Blue Sheep appeared on a nearby ridge, running downslope, presumably to get a drink. The running generated some excitement, as some speculated that a Snow Leopard had spooked them, but I’ve seen Big Horns in Yellowstone run with the same enthusiasm to reach water late in the day. Our guides, meanwhile, are manning several hills, scopes at hand, scanning the slopes for cats.

Day 5, Rumbak Camp.

Surprisingly, my water bottle, kept outside my sleeping bag, did not freeze overnight as it had on our first trip four years ago. Our campsite is situated at the juncture of two valleys, one leading to Rumbak, the other into the mountainous interior where several other valleys join this major valley. Our goal today is to explore this valley, hiking along the frozen river’s edge. Marup, one of our guides, pointed out an old Snow Leopard scrape, but there was no recent sign.

The river we followed is about 150 yards wide, braided with glacial stones, and reminding me of the river at Denali that shares similar features. The valley terminates, or so it appears, in a bowl of mountains, and it looks like only a rise of 300 feet or so would bring one to the snow line. In reality, as distances are so misleading here, it is probably 900 feet. Again, the geology is impressive, with rock folds sometimes forming sweeping S shapes and Z’s, like a blanket or sheet pushed and scrunched on a bed, folding into odd shapes, a miniature of the earth before me.

A side valley joined the broad river valley, leading uphill at a modest incline but taking us deeper into the high country. Most of us took this route, which led to what is now another Home Stay, but once was either a monastery or a warlord’s palace – depending upon the story. Steep cliffs bordered a frozen river that led from this high country, with some areas reminiscent of Goblin Valley, with solid cap rocks compressing the conglomerate rock beneath it, forming spires or very narrow pyramid shapes. A Lammergeir, a huge vulture that is sometimes referred to as a bone-breaker for its habit of picking up large bones, flying high, and dropping the bones onto rocks to shatter the bones for the marrow inside. The Lammergeir flew up the valley, did a U-turn, and flew directly overhead, quite close, and probably only 80 feet above me. I had my Olympus 4/3rds camera and a 150-300 (equivalent 300-600) but the battery apparently was dying and the lens would not acquire focus. In desperation I shot one out-of-focus shot, and then the battery went dead. For the rest of the day I carried the dead weight of several lenses and a useless camera.

A side valley joined the broad river valley, leading uphill at a modest incline but taking us deeper into the high country. Most of us took this route, which led to what is now another Home Stay, but once was either a monastery or a warlord’s palace – depending upon the story. Steep cliffs bordered a frozen river that led from this high country, with some areas reminiscent of Goblin Valley, with solid cap rocks compressing the conglomerate rock beneath it, forming spires or very narrow pyramid shapes. A Lammergeir, a huge vulture that is sometimes referred to as a bone-breaker for its habit of picking up large bones, flying high, and dropping the bones onto rocks to shatter the bones for the marrow inside. The Lammergeir flew up the valley, did a U-turn, and flew directly overhead, quite close, and probably only 80 feet above me. I had my Olympus 4/3rds camera and a 150-300 (equivalent 300-600) but the battery apparently was dying and the lens would not acquire focus. In desperation I shot one out-of-focus shot, and then the battery went dead. For the rest of the day I carried the dead weight of several lenses and a useless camera.

My Lammergeir! Adding this photo is a lame bit of humor.

Continuing on, we reached the Home Stay at 13,670 feet, perhaps the highest elevation I’d reach in the Rumbak area. If this was a warlord’s palace, one has to wonder who he’d be fighting, as the land had to always be rather barren. A Stupa, a stone, dome-like structure, had a few ungulate skulls along a ledge, with one quite out of place. The skull belonged to a Tibetan Argali, a Bighorn Sheep relative that Marup, one of our guides, said sometimes wander into this valley.

At the far end of the valley, and what looked like nearly a mile away, a large ram Blue Sheep stood motionless. Konchok took a photo with his new camera, at 1200mm, and I was absolutely stunned at the size of the image. For an amateur desiring record shots, it’s a great camera.

Our elevation gain to the Home Stay was about 500 feet, on a trail that we took casually, especially when one is just looking at the ground before you. I twisted my ankle, just losing my balance a bit, and it was only then that I really took note of our trail. Most of the time the trail paralleled the stream valley, sometimes thirty feet, sometimes fifty or more feet above the frozen stream. The gradient was steep, at least 70 degrees, so a trip or fall would have been a disaster.

Our elevation gain to the Home Stay was about 500 feet, on a trail that we took casually, especially when one is just looking at the ground before you. I twisted my ankle, just losing my balance a bit, and it was only then that I really took note of our trail. Most of the time the trail paralleled the stream valley, sometimes thirty feet, sometimes fifty or more feet above the frozen stream. The gradient was steep, at least 70 degrees, so a trip or fall would have been a disaster.

The rest of the day’s hike went uneventfully, and we returned to camp in the late afternoon. One of the guys on the trip, a former recon-soldier in the British army, had hiked up another one of the side canyons and found two wolves which he followed for about 500 yards. Unfortunately he only had a 24-70mm zoom with him, but the shots, cropped hugely, were okay, so he’d have had great images with the 200-400mm he still had in his pack.

At 6 all but our ex-soldier were back in camp when we got the exciting news that a Snow Leopard had been spotted. Our guides and spotters were on a small rise just above our camp, and the younger guys in our group practically ran up the hill, probably a 60 foot rise in elevation, and, of course, nearly died by doing so. Exertion, like running, is tough for most of us at 12,000 feet, and they spent the next few minutes gasping. Me, I walked up, as fast as I could, but stopping occasionally, and this time, the tortoise (me) may have won the race, or at least I wasn’t dying from the walk. The young guys recovered fast, nonetheless.

My porter, Konshok, was already setting up my tripod and lens, and as I approached the group gathered around, facing a slope, I worried that the cat was close, and I had missed it. I was wrong on both counts – the Snow Leopard, when one of the spotters aimed my lens at it, was nearly a mile away, and only the top of its head was visible. We put our Swarovski scope on the cat, and I did a Live View with my camera, then magnified that image by 10X, so we had a somewhat decent view of the far away cat. Several people with small lenses or binoculars gathered around my Live View image, and enjoyed a nice view when the cat finally got up, stretched, and walked down the ridge, finally disappearing behind the slope. It was our first cat, and we hoped that seeing this one would break the ice and we’d start to have great luck.

Day 6. Rumbak. We awoke to cloudy skies, with snow threatening the higher slopes. Last evening, as the last guys were leaving the slope, they spotted an Eagle-Owl on a ledge. The owl flew off, but merely seeing one of these birds this high was surprising, as I’ve seen virtually no sign of small mammals for the bird to eat.

Last night I changed strategies for a more comfortable winter survival, camping, night, wrapping the clothes I’d wear the following day around the two hot-water bottles we’re given, and using a hand-warmer in with my batteries. Trying to stack the odds for our luck, I extracted the small plastic Snow Leopard model I’d brought along, and I wore my Snow Leopard goofy hat beneath my baklava, and combined, the two pieces of head gear kept me warm throughout the night.

Our plan today was to hike up the same valley we explored yesterday, hopefully to find the Snow Leopard at a kill. I packed my ice crampons along, just in case, and as it turned out I was glad I did.

We had passed beyond the side canyon we visited yesterday when we received word that something was happening ahead. To reach this destination, most of us crossed the frozen river, which would have been extremely hazardous if not for the crampons. Chitta, one of our guides, told me we had no time to waste on crampons, but I knew my limitations and ignored his advice. Without them, my boots slid across the ice like Bambi on a frozen lake, and I’d have either fallen or jerked myself about trying to keep my balance on the slick ice. With them, the walk was easy and fun, and to insure my gear I held on to Konshok, who like the other guides simply balance themselves and walk across the ice. One slip, however, and my scope and 800mm would be toast, so it was prudent to hold on to Konshok.

As it turned out our destination was the original side of the river, so we crossed the ice once again. I still had no idea what we were after, but I assumed it was a Leopard. Another hiking group had preceded our’s, and they were set up and aiming up a hill. As I approached they motioned for me to get down, so I hunched over and stalked forward until I could join them.

On a distant hillside a Gray Wolf was feeding on a Blue Sheep, with another Wolf lying on a rock further up the hill. We  assume that ‘our’ Snow Leopard had made the kill but the Wolves discovered it and drove the cat off. We watched the wolf from three hundred yards or so, and with at least two groups lined up it was impossible to even attempt to get closer. Eventually the wolves took off with pieces, one taking a leg, while the other Wolf carried the remains of the carcass – head, neck, and at least the front half of the body – up a steep scree slope, seemingly effortlessly, and disappearing from sight.

assume that ‘our’ Snow Leopard had made the kill but the Wolves discovered it and drove the cat off. We watched the wolf from three hundred yards or so, and with at least two groups lined up it was impossible to even attempt to get closer. Eventually the wolves took off with pieces, one taking a leg, while the other Wolf carried the remains of the carcass – head, neck, and at least the front half of the body – up a steep scree slope, seemingly effortlessly, and disappearing from sight.

With the wolves gone we had lunch, as the distant slopes became shrouded in snow clouds, weather that soon reached us. The camp staff carried up lunch, tea, soup, bread, and some meat, while the porters gathered whatever vegetation they could find, and yak dung, to make a fire where they heated their food and squatted around, warming their hands. It began to snow heavily, and with the low cloud cover that we had all morning I doubted if Mary would be flying in to Leh to join me for our trip to Ulley. The ex-soldier and one of the other younger guys in our group, a former Ironman competitor, decided to go for the wolves, and after lunch hiked up the steep mountainside. Eventually they reached the very top of the ridge where they looked down, very far below, on the Guest House we visited yesterday. The view was impressive, the isolation sublime, and that hike, for them, was one of the trip highlights.

With the wolves gone we had lunch, as the distant slopes became shrouded in snow clouds, weather that soon reached us. The camp staff carried up lunch, tea, soup, bread, and some meat, while the porters gathered whatever vegetation they could find, and yak dung, to make a fire where they heated their food and squatted around, warming their hands. It began to snow heavily, and with the low cloud cover that we had all morning I doubted if Mary would be flying in to Leh to join me for our trip to Ulley. The ex-soldier and one of the other younger guys in our group, a former Ironman competitor, decided to go for the wolves, and after lunch hiked up the steep mountainside. Eventually they reached the very top of the ridge where they looked down, very far below, on the Guest House we visited yesterday. The view was impressive, the isolation sublime, and that hike, for them, was one of the trip highlights.

As we ate up the time after lunch I studied the landscape, which looked as if it could be on Mars. The land is barren, with a thin, straw-like grass covering some areas, and a tiny, tumble-weed plant that added a bit of orange-yellow color, and the only cover, on the scree slopes. In summer, I suspect goats and sheep graze here, but the grazing must be poor and the living very, very hard.

The rest of us slowly made our way back down to camp, as the snow fell, making footing somewhat treacherous. Shortly after reaching camp it stopped snowing, but the day remained cloudy. The day, now sunless, grew cold and I put on everything I had, as snow continued to intermittently fall through the evening and throughout the night.

Day 7. Rumbak to Leh

We awoke to about an inch of snow covering the tents and ground, the conditions we wished we’d had for the entire week of camping. Without snow, the Blue Sheep stay high on the ridges, as do the Snow Leopards, and now, with near perfect conditions we’re heading back to Leh. In theory, if the guides spotted anything we’d delay our departure and photograph, but since our taxis were already booked I suspect that there wasn’t too much effort spent in searching for cats. We left camp around 9:30, packed up and ready for the horses to arrive.

Hiking out, we had snow, and visibility was very limited. While the trail never seemed dangerous, the fact is that we were often on slopes that would pitch an unwary hiker thirty or fifty feet down onto the rocks or stream below. I paused often to scan the hillsides, or cliffs, but saw nothing. It took only an hour or so to reach our original camp site, still deserted, and with no animals visible on the slopes above.

Our trip back to the car park from this camp required another hour or so, and we arrived long before our scheduled pickup time. The road here was icy and snow covered, and I wondered if our taxis would make it up the hill. The entire return was a fairly effortless walk since most of it was downhill. New groups were hiking up as we headed down, and one guy, in his fifties or sixties and appearing a bit over-weight, looked like he was really suffering, and this only a few hundred yards up from the car park.

We waited nearly an hour before the first taxi arrived, and in a not very encouraging introduction the vehicle slipped and stayed stuck on the final stretch of roadway. With the help of guides and porters they pushed the taxi free, and, thankfully, started chaining up the tires for our return to Leh.

Sanzkar river and Indus – intersection.

We reached Leh in time for a late lunch. I turned in laundry, racking up a $60 bill, but well worth it, as I couldn’t imagine putting on the same, five-day old clothes, for another two days in Ulley.

Day 8. To Ulley

We left Leh at 9:30AM, planning a long drive to Ulley where, en route, we’d stop to scan for Snow Leopards. On our drive we encountered a nice herd of Urial Sheep, and we left the road for about half-frame shots. Snow covered the north and east facing slopes, and south and west the rocks were bare. The sky was crystal clear, and I was relieved, as with the bad weather yesterday Mary’s flight was cancelled and she wisely chose to remain in Delhi for the next three nights, rather than join me and be at 13,000 feet almost immediately.

We arrived in Ulley in the late afternoon, and unlike last year, when we had snow leopard tracks along the road, the snow was track-free. After settling in, our guides took positions at several vantage points and scanned for cats, but we saw none. Instead, a difficult-to-see herd of Asiatic Ibex grazed far above us.

Day 9. Ulley

Day 9. Ulley

The Home Stay is quite a bit more pleasant than camping. Our rooms had electric heat – portable heaters we were asked to turn off at night, but in the evening hours the heaters helped warm the rooms. Phil, Gordie, and Tommy shared one large room, that also functioned as our meeting area and dining room. Danni and Steve and Andrew were in adjacent rooms, and all shared an outdoor bathroom where toilet seats – versus squatting – were provided. I was staying in a guest room in the main house, and used the family’s facilities, a slit I trench in a walled enclosure, with no roof and a good view of the rooftop of the house nearby.

After breakfast we drove, thankfully, uphill to the last house on the hill, a location we hiked to four years ago. The road was snowy and icy in spots, and required fording a stream that was mostly frozen. However, the drive took us to the highest country, before we continued on, on foot, climbing a rock outcrop for another 700 feet or so. We were looking for snow leopards and ibex, and at 14,600 feet we stopped, as the route higher from that position was too treacherous. We were on snow and rock, with the rocks composed of a sandstone-like conglomerate, appearing to be solid rock but with a gravelly sheen that sometimes slipped, causing treacherous footing. Chitta cautioned us to go no higher by that route.

We could see Ibex, about a mile away and further up slope, and while I was at a higher position Steve, Andrew, and Marup decided to try for the Ibex. To do so, they had to descend the rocks, then climb uphill again, and when I finally saw them, I felt the effort would be useless. Chronic dry sinuses and a developing chest cough didn’t help in my decision, but I didn’t think Steve would be successful. Tommy decided to join them and started down and across the rocks. The going, Steve reported, was tough, with the rocks often snow-covered, and the ground frozen solid and slick. Under Steve’s urging they continued to move closer, and to my amazement the Ibex didn’t seem to mind. Chitta, the guide who remained with us, thought that the Ibex would run high, or to our right, or perhaps to our left, where they could come close to us. They didn’t do any of those choices, and instead continued to graze. Eventually, Steve, with a 600mm and 2X converter, captured nearly half-frame shots of the Ibex, so the effort was certainly worth it.

When everyone returned to the Home Stay, I casually remarked to Marup that they had had great luck, and I was surprised that the Ibex didn’t run off. Marup replied that he had called the owner of the Home Stay, who told him that the Ibex used to be wary, but now were fairly tame and approachable. I didn’t ask our guide when he learned that information – was it during the hike to the Ibex, was it before they even started, or was it on their way down – but either way, it was too late for the rest of us to consider going for the Ibex. And for the three who made the hike, covering rough country that may have been avoided – as their hike down was direct, easy, and on a gradual slope, knowing that an easier route may have been possible was a bit annoying.

We spent the rest of the afternoon either relaxing or glassing the slopes for cats, while our three guides, and my porter, spent the entire time at the scopes, as the light dropped, a wind picked up, and the cold descended. Only after the sun dropped below the mountains, and the light was gone, did they quit – I was very impressed with their efforts.

Day 10. Ulley to Leh

The plan was, if nothing was spotted from Ulley we’d slowly drive back to Leh, pausing often to scope the hillsides for snow leopards. Yesterday, a hiking group had been dropped off at Ulley, where the group would then descend the trail paralleling the stream valley and eventually meet their vehicles below. One of the group told me that just a half hour after they had started their trip they had had an hour’s viewing of a snow leopard basking on a ledge, with the cat finally standing and climbing the ridge and passing out of sight. I later learned that their location was where we had our lunch on our way to Ulley, a great location with wide-open views. I didn’t ask how close they’d been to the cat – I didn’t need to know.

Although we stopped at a few locations, the plan, I felt, was a bust, as we arrived back in Leh around lunchtime – not late in the afternoon as I’d have expected. We had no significant sightings of wildlife on the way back, but I think everyone was, by then, tired and accepting of our outcome.

For snow leopards, this trip, this year, was disappointing, as we only had one sighting, and our record was somewhat typical of the luck people were having this year. The culprit – no snow, and the sheep and the cats were high. For the other wildlife, the Pika, Urial, Blue Sheep, Ibex,Wolves, Lammergeir, and Chukars, we were more successful than last year, and everyone felt the trip itself was a success, as the landscape, the company, and the experience was worth it.

After this trip, Steve and I continued into central India, for what would turn out to be an extremely successful mini-Safari for Tigers.

Trip Report:

Snow Leopard

Photo Expedition

Trip Report

2016

That was it. Our snow leopard. Once again, the lack of snow kept the Blue Sheep and the Snow Leopards high in the high country. This leopard killed a sheep during the night, but wolves stole the kill, depriving us of any chance at getting close to the leopard. Scroll down to read the details and to see more images.

Before you see this elusive cat, tradition holds that the cat is only referred to obliquely, as ‘The Gray Ghost,’ or ‘The cat that shall not be named,’ as calling Panthera oncia by its common name might bring bad luck. Calling it the Gray Ghost is most appropriate, I think, as it truly is a phantom. In a land of towering mountains, sheer cliffs, and endless vistas of rock and snow, finding the Snow Leopard seems impossibly daunting, and seeing one seemingly is miraculous.